Measurement of π+ Production by Neutrinos in MINERvA

Studying neutrino interactions with matter

What happens when a neutrino collides with matter?

A neutrino collision with a common material (e.g. carbon or lead) is very complicated, and fundamental theory can only tell us so much before its predictions become too difficult to compute. Experimentalists like myself study these collisions in order to guide effective theories or optimize fundamental prediction-making. There’s still a lot to learn.

Why care?

The details of neutrino collisions are interesting in their own right, and they could well be foundational technology for a future starfaring human civilization. Until then, the physics community’s excitement in neutrino interactions is in the key role it plays in understanding another, even stranger, property of neutrinos: oscillation.

In neutrino oscillation, a neutrino of one type can spontaneously morph into another. The 2015 nobel prize was awarded to a team that proved neutrino oscillation happens, and we’re now eagerly studying how and why. It’s no exageration to say that these oscillation mysteries have bearing on the foundations of the universe itself – why it is the way it is, and why it exists at all.

And it all relies on precise knowledge of neutrino collisions.

Neutrino interactions

Studying neutrino collisions is like studying the video of a car crash test and wanting to know exactly which piece of the car will fly off in which direction and at what speed. What kind of car is it? How fast was the car moving? At what angle did it collide with barrier? Did it ricochet off the side or head on? There are many ways a neutrino collision can go down, and they depend on numerous variables and complex nuclear physics.

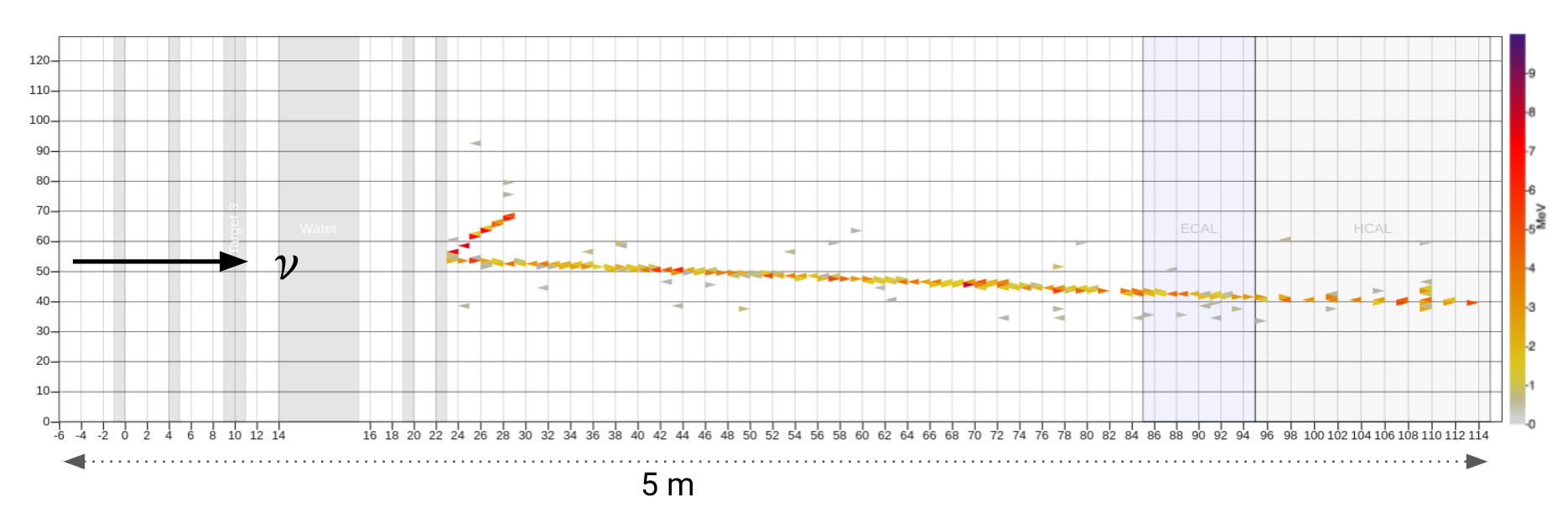

We study neutrino collisions by sending human-made neutrino beams into a particle detector to capture time-segmented images of interactions. Like a car crash test, collisions can be too complicated to know exactly what happens in each case. We break the problem down statistically by separating collisions into relatively broad categories, e.g. head-on vs side ricochet.

My work singles out collisions which simply produce two debris particles: a pion and a muon.

The MINERvA experiment collected tens’s of millions of neutrino events in our dataset, and I’ve written software to search for pion events, like performing forensics on a crash test. On ten’s of millions of crash tests. I look for statistical trends in the wreckage to learn, as precisely as possible, how each crash went down.

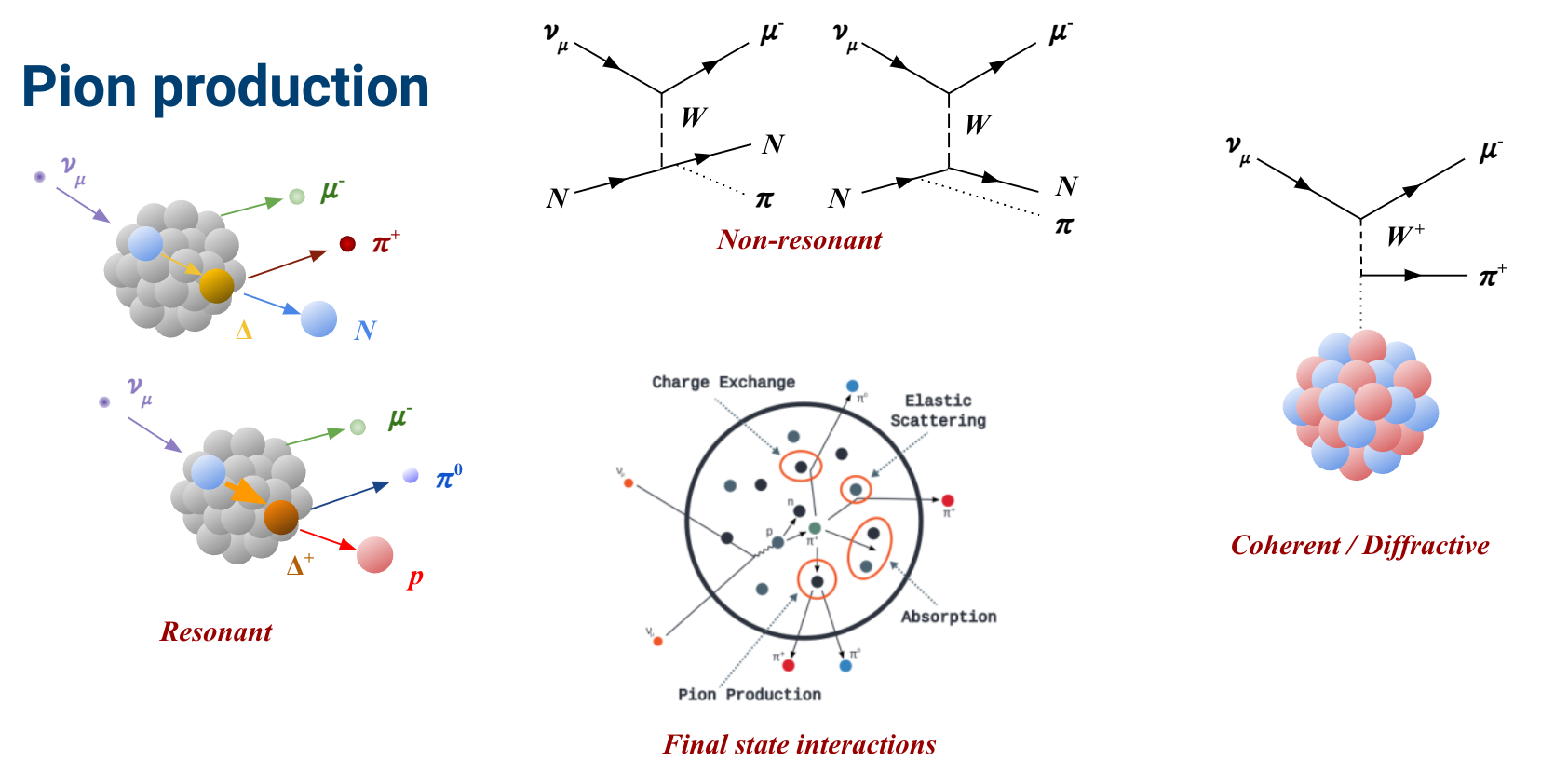

Neutrino-induced pion production

My analysis software looks at each of the millions of images, performs forensics, and tries to separate the pion events from the rest. The end goal is to compare the measurement with a theoretical prediction, for example of how many events are produced by the numerous pion production mechanisms. Disagreements between data and prediction can provide hints to theorists about which processes need to be reevaluated.

What’s new?

- I wrote my thesis on this topic, and now I’m preparing results with collaborator Everardo Granados (University of Guanajuato, MX) for early 2024 publication.

- I spoke about pion production at the European Physical Society Meeting in Hamburg, DE in August ‘23.

- My codebase is public here, and MINERvA is planning to release our data to the public in 2024.